Smart as dogs are about some things, they’re not always noted for their intellectual prowess when it comes to investigating dangerous animals.

Porcupines, for instance.

More often than not, dogs rush in where fools fear to tread, getting a face full of sharp quills for their trouble.

The North American porcupine is aptly named. His scientific name, Erethizon dorsatum, loosely translates to “animal with the irritating back.” He is the continent’s second-largest rodent, weighing as much as 40 pounds. While a porcupine’s first notion when attacked is to climb a tree, he’s fully capable of defending himself when necessary.

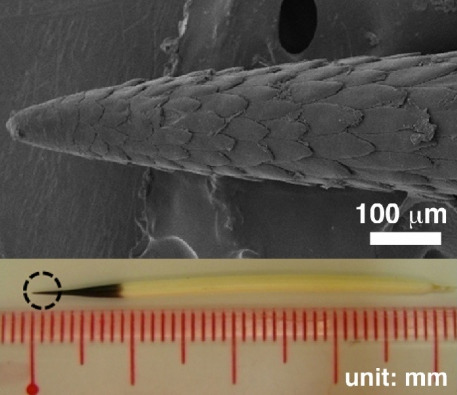

An angry and defensive porcupine raises his quills (which are actually modified hairs) and lashes his tail. When the tail makes contact, usually in the face of an unsuspecting dog, the loosely fastened quills become painfully embedded in the dog’s skin — most often in the tender mouth and nose. Once lodged in the skin, the barbed quills are difficult and painful to remove. (A porcupine has approximately 30,000 quills on his body, and, no, he can’t launch the spines through the air.)

Quills do more than damage the area where they enter the body. Their barbed tips mean they can only move forward. Quills can migrate from where they enter to any place in the body, sometimes causing fatal injuries.

“I’ve seen patients with septic peritonitis [infected abdomen], and you open them up and there’s a porcupine quill that has poked through the bowel,” says Tony S. Johnson, DVM, an emergency and critical care specialist at Purdue University College of Veterinary Medicine in Lafayette, Ind. “One dog who died suddenly had tangled with a porcupine a few months before. When they did an autopsy on him, he had a porcupine quill that had poked through his heart. It bled into the sac around the heart.”

Even a tiny inch-long fragment can cause problems. If it’s under the skin and starts to migrate, there’s no way to find it.

If you have visions of pulling the quills out at home with a pair of pliers, think again. Removing the quills is a lengthy, laborious, and risky process that is best done with the dog under general anesthesia. It can take an hour or two for a veterinarian to remove them, all the while hoping the quills don’t break off.

“You’ve got to be able to really look in the mouth and the back of the throat,” Dr. Johnson says. “You don’t want to leave a fragment that migrates.”

No particular breed is more likely to take on a porcupine than another, but, “the dog most likely to” tends to be large and territorial. Dogs who get riled up about other animals coming onto their property are usually at risk. If you live near porcupine habitat — forests, desert, rocky outcroppings, and hillsides — walk your dog on a leash and bring him in at night to avoid run-ins with the nocturnal critters.

Most important, be able to identify a porcupine quill. Dr. Johnson recalls a case he encountered when he was practicing in California.

“A lady called and said her dog had tangled with a porcupine,” John says. “She had tried to pull out the quills, but it was painful, so she wanted to bring the dog in and have it done under anesthesia. When she arrived, it turned out she had been pulling out the dog’s whiskers. They were not porcupine quills at all.”

Your dog will thank you for knowing the difference.